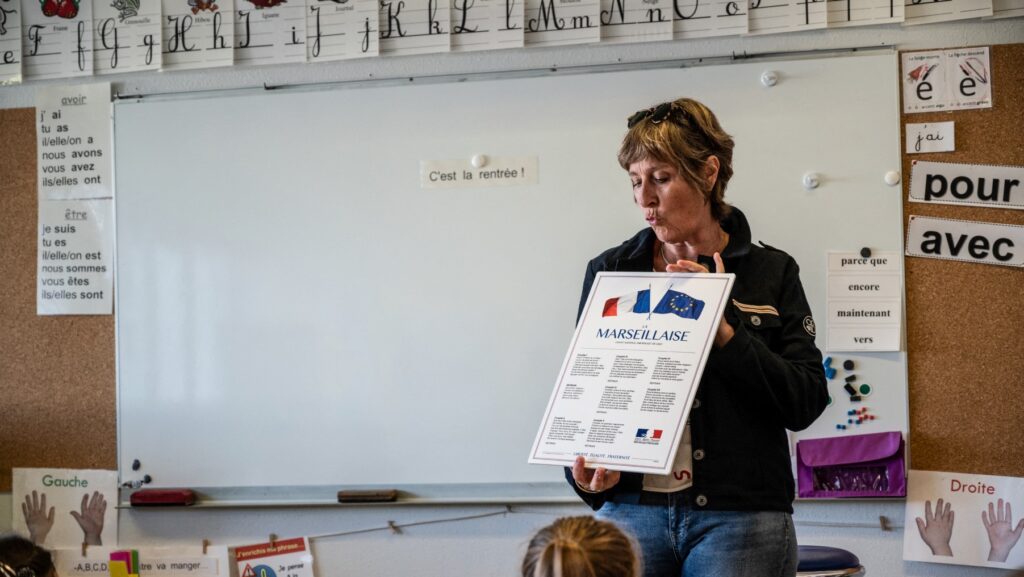

Children sit in their classroom on the first day of the start of the school year, at the Jules Ferry de la commune elementary school in Aytre, western France on September 2, 2019, as they are taught the words of the French national anthem ‘”La Marseillaise.”

Xavier Leoty / AFP

The start of the new school year in early September in France took place in an atmosphere of gloom unlike anything seen before. Among both teachers and pupils, motivation is close to zero—such is the state of disrepair of the school system.

Since the second half of August, the press has been flooded with reports of teachers on the verge of resigning or suffering from depression, not to mention articles about knife attacks, even between teachers, and suicides among educational staff.

Once again this year, recruitment difficulties have reached new heights. How can this be surprising? On the Right, people have long since stopped paying tribute to the figure of the teacher as a dispenser and transmission of knowledge. In ‘good’ families, people have long since fled the national education system, seen as a ‘nest of leftists.’ Beyond ideology, the ultimate argument is violently imposed: being a teacher is poorly paid. But on the Left, the teaching profession is no longer attractive either, even though it was once one of the glories of left-wing activism in France to take care of young people and their education. The erosion of both buildings and respect, and the reign of mediocrity have reached such a level that even the Marxist workers sent to harvest minds have failed to ensure their own succession.

How can anyone want to teach when those who have chosen this path are confronted daily with mediocre salaries, ugly and dilapidated buildings, a deaf and blind hierarchy, unruly pupils and violent parents? The list of grievances is long and continues to grow.

What has a crushing effect on the morale of teachers who, at all costs, are still trying to hold on is the desperate lack of solutions coming from above. For several years now, French education has been falling into a bottomless abyss, and the arrival of former Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne, whose priority in this disastrous month of September was to remove gender references from the Pantheon motto, is not going to change anything.

The union rhetoric is well-honed, and its denunciation of state inertia follows strict codes. There are constant protests against the ‘lack of resources’—even though education is the state’s largest budget item, and one that is dramatically misused. They never tackle what should inspire a real revolt: the destruction of knowledge transmission, the sacrifice of children on the altar of pedagogical ideology, and the way in which schools inevitably inherit the ills that afflict French society as a whole.

However, this year, things seem to be changing. Timidly, between the lines, some observers are finally daring to name things. Published at the start of the school year, Main basse sur l’Education nationale (A Strong Hand on National Education), the book by Joachim Le Floch-Imad, teacher and director of the ResPublica foundation—a think tank created by former sovereignist minister Jean-Pierre Chevènement—renews in 2025 the grievances written year after year by so many teachers dismayed by the collapse of the education system.

In France, his testimony has shaken the educational world because, as a teacher, he didn’t just lament the crisis—he carried out a genuine investigation into how the administration’s “renunciation, amateurism and blindness” block any educational breakthrough.

As Le Figaro analyses, “too many books on national education are content to take stock of the situation and point to the breakdown of society as the cause of the failure of the school system. Joachim Le Floch-Imad has the courage to name the culprits.”

The book bluntly holds those working in education responsible for their own misfortune. And it finally dares to say the unspeakable: if it is becoming increasingly difficult to teach in France today, it is because children have changed.

🚨 🇫🇷 ALERTE INFO : Élisabeth Borne a ouvert les portes et accueilli les élèves de l’école Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, dans le 15ᵉ arrondissement de Paris. Où sont les Français de souche ? pic.twitter.com/oCASUsWdN1

— Wolf 🐺 (@PsyGuy007) September 1, 2025

Mass immigration cannot fail to have an impact on academic standards.

With more than one in five Year 5 pupils speaking a language other than French at home and 41.6% of under-4s being immigrants or of immigrant origin (INSEE), immigration is profoundly transforming our schools. It is not the only cause of their decline, but it amplifies all the difficulties. In particular, immigration increases the heterogeneity of classes and lowers the average level, both in our country and in 70% of OECD countries.

Waiting lists for private education have never been so long, and the number of enrolment refusals never so numerous. Accessing private education is precisely an attempt to escape the inexorable multiculturalism imposed on families. For the Left, this is proof that private education is racist. Pressure is mounting on state-subsidised private schools, which have the merit of offering basic guarantees to worried parents who just want their children to have a teacher in front of the blackboard every day—and not risk being hacked to death with a machete on their way out. This pressure is not without consequences for these so-called private schools: mostly Catholic, they are forced to increasingly dilute their own identity in the face of demands from parents who, more often than not, are not looking for an educational project in line with the values of the Catholic Church, but simply a school that works. Those who try to defend their “unique character” and Catholic ethos tooth and nail are subjected to the scorn of the press and the left-wing political class.

The solutions to escape this hell are well-known—perhaps too well-known. But the very possibility of implementing them is doubtful. Forgive us for this pessimistic assessment, but the stranglehold of the unions on the educational institution is such that no reform can be seriously and effectively implemented at this time. The lesser evil remains to allow what works to continue to do so, to let a handful of places where knowledge is authentically transmitted flourish—which will, when the day comes, constitute the fragile refuges of civilisation.