In letters to the main figureheads of NATO, the European Union, and the United Nations, Athens is sounding the alarm. If a Ukraine-like imbroglio is to be averted, Turkey needs bridling, the letters warn, asking that these institutions formally condemn the recent rhetoric coming out of Ankara.

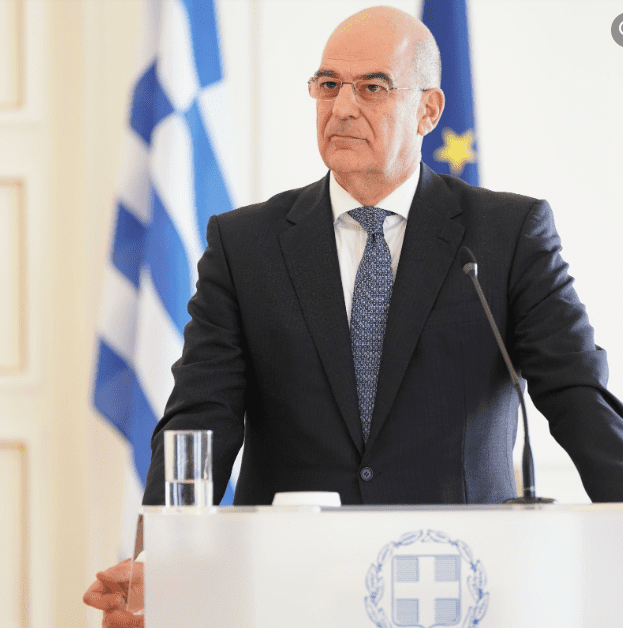

According to the Associated Press, which was allowed to look into the letters’ contents Wednesday, September 7th, Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias demanded that his country’s rival—and, paradoxically, fellow NATO ally—should be curbed in its territorial assertions.

The letters, which had been sent out earlier this week, also complained about comments by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who had called the Greek people “vile.” These were “unprovoked, unacceptable and an insult against Greece and the Greek people,” and should be condemned by all three bodies, Dendias asked.

“By not doing so in time or by underestimating the seriousness of the matter, we risk witnessing again a situation similar to that currently unfolding in some other part of our continent,” he wrote, clearly alluding to the present Ukrainian conflict.

On September 5th, Erdoğan ramped up his rhetoric against Greece, in response to what Ankara considers to be an alarming military buildup on the “occupied” Greek Aegean islands. Since these, which have been part of Greece for decades, are close to Turkey’s coastline, he resorted to the barely veiled threat, saying “we can come down suddenly one night when the time comes.”

During a visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina this Tuesday, Erdoğan complained that the neighboring Greeks had “islands in their possession, they have bases on these islands; if illegitimate threats against us continue based on them, our patience has a limit.” Athens subsequently decried Erdoğan’s remarks as “openly threatening,” and said it was ready to defend its sovereignty.

In a letter addressed to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, Dendias voiced concern that the fraught state of Greco-Turkish relations might weaken the alliance’s integrity.

“The Turkish attitude is a destabilizing factor for NATO’s unity and cohesion, weakening the southern flank of the Alliance at a moment of crisis,” he said, adding that Greece is “currently witnessing one of its worst periods in years.”

Suggestions that Erdoğan might be cynically employing such rhetoric in order to fire up voters for an upcoming general election in June 2023, Dendias flatly rejects. The “nature and tone” of Erdoğan’s remarks are “more than obvious,” and dispel “any doubts as to their intended purpose,” he said. Like Turkey, Greece will be holding an election of its own, a month later.

The EU had already expressed concern over the Turkish leaders’ comments, while the U.S. State Department called them “unhelpful,” as it reiterated that Greek sovereignty over the Aegean islands is “not in question.”

Earlier this month, on September 1st, Ankara had delivered letters of its own to the EU, NATO, and the UN, accusing Greece of engaging in “unlawful actions” and making “maximalist demands” in the Aegean.

Despite sharing a NATO membership card, the neighboring countries do not see eye to eye on a host of issues, which include maritime boundaries (disputes encouraged by the presence of energy reserves in the eastern seas) and claims on Cyprus. Such present obstacles are made even harder to overcome due to the historically rooted acrimony between both powers.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February, Greece and Turkey have been wooing the U.S., in a bid to become its favored regional ally.

With respect to the war, Ankara has remained ambiguous regarding its true loyalties. It did not join the West in slapping sanctions on Russia; instead, it positioned itself as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine. As it welcomed both Russian exiles and Ukrainian refugees, while supplying Kyiv with drones, Turkey’s strategy made a positive impact, since it was able to broker a deal so that Ukrainian grain exports could recommence.

Yet Ankara’s diplomatic high-wire act did not provide the expected payoff. To the Turks’ dismay, last May Greece won out, as it signed onto an open door policy with the U.S., granting its military full access to key bases.

Soon after, Erdoğan cut off all bilateral talks with Greece after Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis urged the U.S. to discontinue arms sales to his country’s regional competitor. A series of military provocations followed, creating a highly combustible situation not seen since 2020 when Turkey conducted energy exploration in waters claimed by Greece.

As previously reported by the European Conservative, only last month Greek fighter jets were scrambled to dissuade Turkish jets from approaching the island of Rhodes. Ankara immediately termed it a “hostile action,” as it said its fighters were flying in international airspace—a claim which was subsequently denied by Greece’s Defense Ministry.

In a separate statement last Tuesday, the Greek foreign minister accused Turkey of having carried out 6,100 airspace violations this year alone. Almost daily now, Greek fighter aircraft are called to the skies to identify and intercept Turkish military planes. Occasionally, simulated dogfights flow from this, which has cost several pilots their lives in the past decades.