Back in October, I issued a warning that Europe is facing another widespread debt crisis. Country after country is showing serious signs of a combined fiscal and political crisis. France, the most urgent crisis case right now, recently suffered an extraordinary credit downgrade precisely for not being able to bring an end to the country’s fiscal and political stress. As I noted back in September, the French situation is so bad it cannot be ruled out that the country goes down the same disastrous path that Greece took 15 years ago.

Germany is only a small step behind France on the crisis path. The red fiscal flag has also gone up in Slovakia, but even when a government manages to balance its budget—as in Portugal—the joy is shortsighted and temporary due to the methods used for closing the deficit gap.

As I explained in my Europe-wide warning, these countries are only a few examples of the widespread debt-and-deficit problems. Today, we can amend the fiscal-political crisis list with yet another example. Euractiv has the story from Belgium:

Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever gave his deadlocked ruling coalition more time to agree a cost-cutting budget on Thursday, staving off fears of an imminent government collapse. The straight-talking Flemish conservative—who only became premier in February after seven months of painstaking negotiations—set a new 50-day deadline to strike a deal. That came after he had sought to pile pressure on his governing partners by dangling the prospect that he could resign over the failure to agree through 10 billion euros ($11 billion) of savings by 2030.

This budget problem is growing urgent in Belgium; if I lived there, I would expect austerity packages to be rammed through parliament in the coming months. Spending cuts will come, and there is an elevated risk that they will be increasingly aggressive.

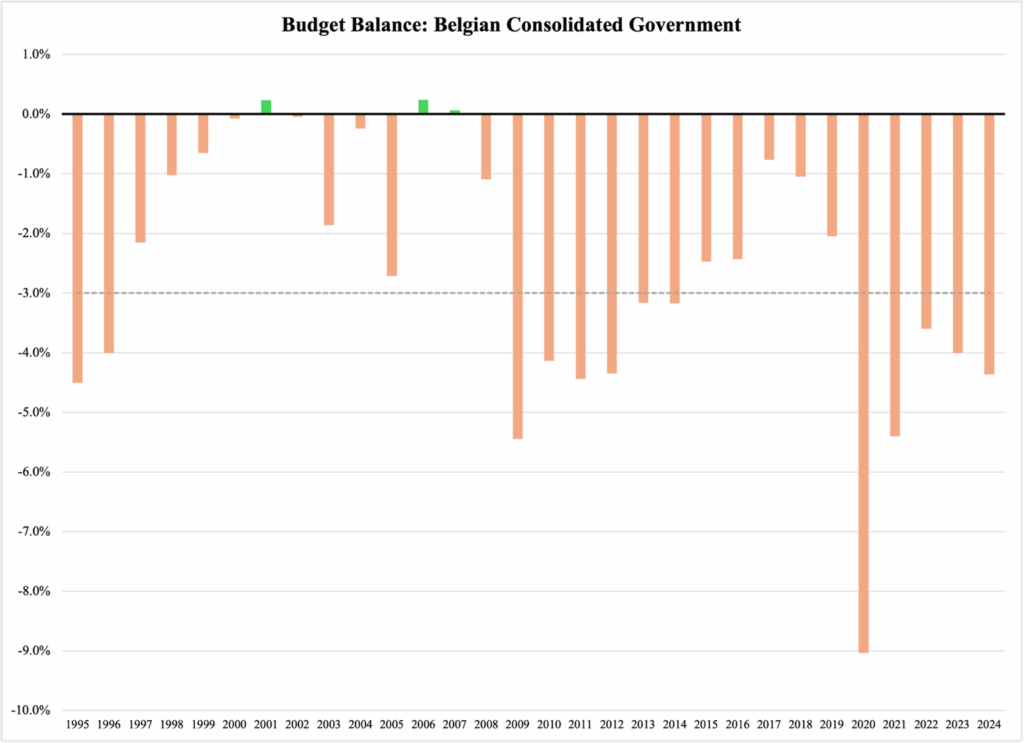

At the same time, none of this should come as a surprise. Figure 1 reports the fiscal balance for the consolidated government sector going back 30 years:

Figure 1

As the gray dashed line shows, on 13 occasions since 1995, Belgium has violated the EU’s deficit-to-GDP cap. Enshrined in the notorious Stability and Growth Pact, this cap maximizes a nation’s consolidated public-sector deficit to 3% of GDP.

To make matters worse, the recent trend is negative, and the bulk of the problem is in the hands of the central government. Euractiv again:

Talks over the new budget have already dragged on for several months, missing a number of self-imposed deadlines. De Wever says the spending cuts are vital to help reduce Belgium’s eye-watering national debt, one of the steepest in the European Union.

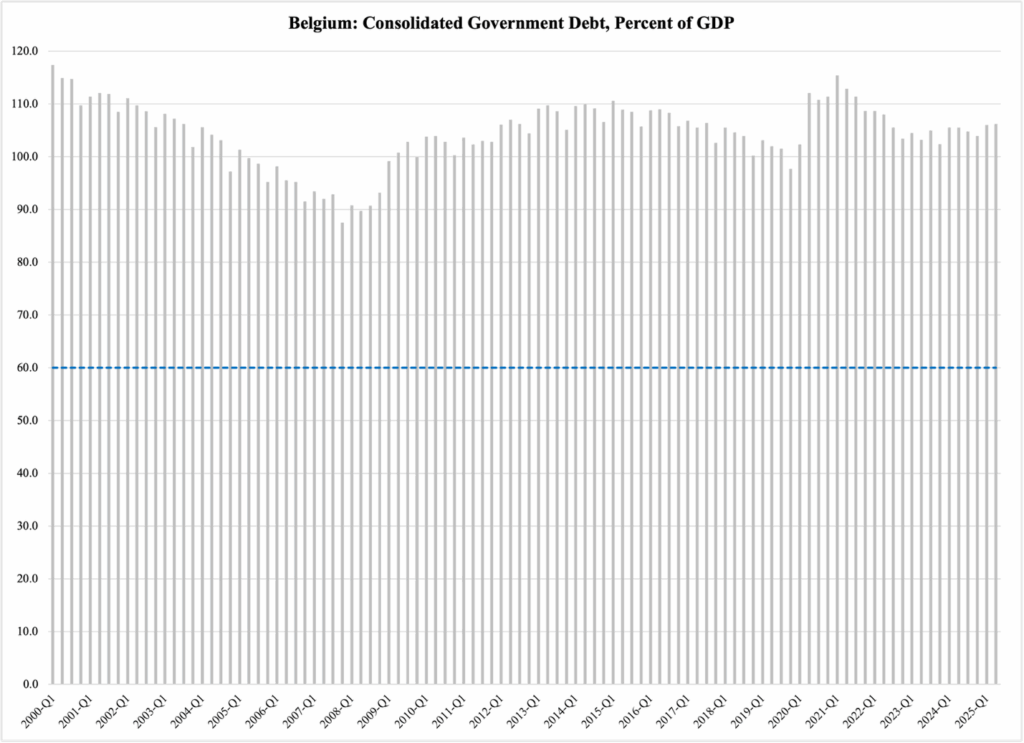

Yes, the Belgian debt-to-GDP ratio is indeed eye-watering:

Figure 2

Over the past 25 years, Belgium has not even been close to complying with the Stability and Growth Pact’s requirement that government debt not exceed 60% of GDP (the dashed blue line in Figure 2).

The reason why the Belgian government is an endless fiscal trash bin is no different from other European countries. Of the 53.3% of GDP that the government in Belgium spent in 2023, two-thirds went toward programs for economic redistribution. In short, the socialist welfare state:

Figure 3

The two-thirds share for the welfare state is a standard figure for Europe, but it does more harm in Belgium than in many other countries due to the fact that their government as a whole—spending more than 53% of GDP—is bigger than average.

One of the unmistakable consequences of this large, redistributive welfare state is that it gradually suppresses GDP growth. To take one example, programs categorized as ‘social protection’ pay out benefits to lower-income families (and to families and individuals with no income). These benefits discourage workforce participation:

Welfare state programs, costing Belgian taxpayers almost €214 billion in 2023, also require taxes. Depending on the profile of the tax system, its burden on the private sector can be more or less discouraging to economic growth. However, when total government spending exceeds 53% of all economic output, it does not matter as much anymore how the tax system is configured; the sheer burden of taxes is enough to depress economic activity.

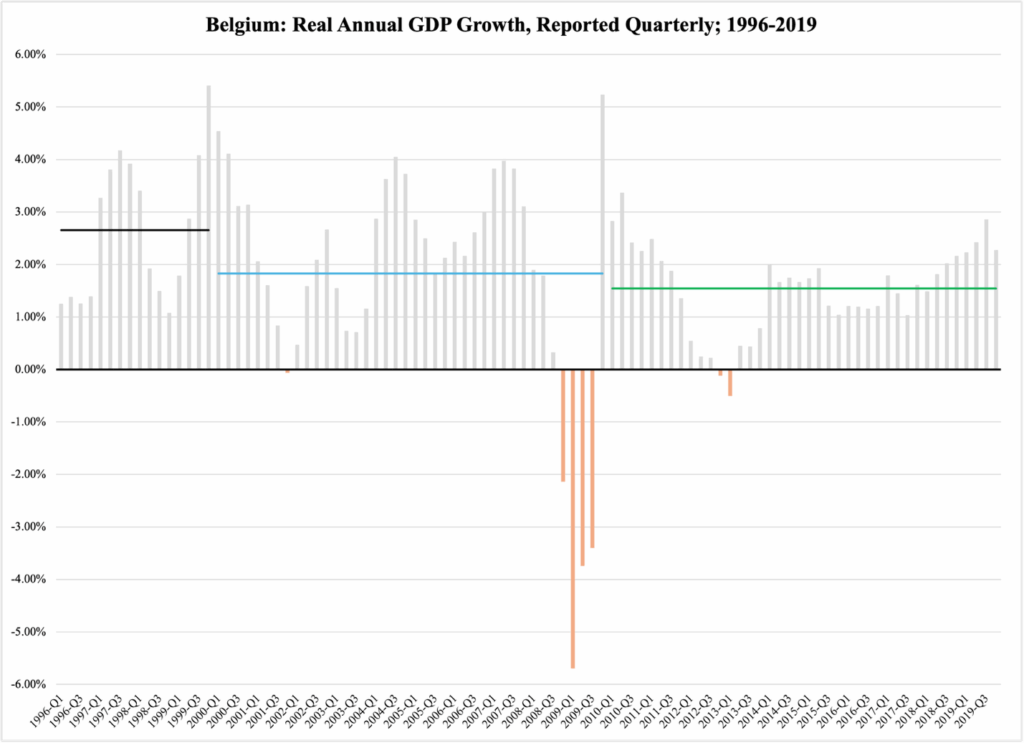

Figure 4 confirms that the Belgian tax base—the gross domestic product, or GDP—has gradually drifted toward stagnation:

Figure 4

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The three horizontal lines illustrate the structural decline in GDP growth. The black line, covering the late 1990s, shows that the Belgian economy expanded at almost 3% per year, adjusted for inflation. The blue line, representing the first decade of this century, shows the economy not even reaching a 2% growth, although there were a couple of peaks in the vicinity of 4%. Lastly, the green line shows how, in the 2010s, the Belgian economy consolidated its stagnant character: growth averaged just a smidge more than 1.5% per year.

A stagnant economy means stagnant tax revenue. When the economy stagnates, relatively more people qualify for social benefits. By the same token, the stagnant economy discourages productive economic activity. The former leads to an upward pressure on government spending, while the latter leads to a downward pressure on tax revenue.

The Belgian government has no less of a challenge ahead of itself than its peers in Germany, Greece, France, Slovakia, Sweden, Spain, the Netherlands, or Portugal. The only way to solve this structural budget crisis is to radically reform the welfare state, i.e., replace its purpose of economic redistribution with a purpose of preserving the nation and its economy.